Payment Protection Insurance: Thematic review

4 March 2018

Mis-sold payment protection insurance (PPI) claims have been a feature of the legal market since 2011, when the High Court ordered lenders to repay customers who had been sold products which were unsuitable for them 1.

Although a free and straightforward process exists for customers to make claims themselves, both claims management companies (CMCs) and regulated firms work in this area.

The Financial Guidance and Claims Bill, due to become law in mid-2018, will impose an interim PPI fee cap of 20 percent of redress plus VAT applying to CMCs and other regulated businesses, to be enforced by relevant regulators.

We issued a warning notice in 2017 highlighting concerns about the practices of some firms working in this area, while also stating that charging more than 15 percent could be considered unreasonable, unless justified by the work and risk involved.

This warning notice was further to previous guidance for users of legal services (issued in 2011) and for firms (issued in 2012).

The Financial Conduct Authority (FCA) has imposed a deadline of 29 August 2019 for the final PPI claims to be made.

Our thematic review involved visits to 20 firms. While this is a small sample in terms of the overall legal profession, it is a significant proportion of the relatively low number of firms we believe are actively involved in regular PPI work on a day-to-day basis.

Although the number of firms involved in this market may be small, they collectively handle claims worth hundreds of thousands of pounds, with the largest single claim identified while researching this thematic report was worth more than £25,000.

Headline summary

- Our review of law firms working in PPI found a mixed picture. There were a number of areas of good practice, but we found poor practice from individual firms. Our major area of concern is around charging.

- We found that four out of five firms are routinely charging fees of more than 25 per cent, with some charging as much as 50 percent of the total claimed for clients.

- This is despite our notice last year warning firms that we did not expect firms to be charging more than 15 percent without good reason. We expect firms to treat clients fairly and work in their best interest. Although some firms could provide good evidence as to the reason for higher charge and it being proportionate to the work carried outs, others could not.

- The government's proposed interim fee cap of 20 percent is likely to resolve this issue, and will apply regardless of risk or complexity. This, combined with the 2019 deadline for PPI applications, is likely to lead to further specialisation and to more firms exiting the market.

- We did find good practice. For instance, firms generally had a high level of client contact and most informed clients at the outset that they could make a claim themselves. Firms also generally had processes in place to check that CMCs were sourcing clients appropriately.

- Although we did not find any current evidence of cold-calling, we did find a historical example. This is banned under our rules. It is a serious issue, and we will take action where we find evidence of it.

- We will take action against firms where we have found serious poor practice. Eight firms have been referred in to our disciplinary process.. Yet given the impending deadline, the limited number of firms in this sector, a proposed government cap and likely further shrinking of this market, we are not planning additional proactive regulatory action or a further review of this area.

Key findings of the thematic review

New clients

- The majority of firms took care to tell clients that they could make a claim for themselves.

- Firms told us that they largely relied on referral/introducer arrangements with CMCs (60 percent) and online advertising (50 percent).

- One firm admitted that it had historically cold-called clients, but no evidence of cold-calling was found apart from this. This is a serious issue, and we will always take appropriate action when we find evidence of this.

- The vast majority of files we reviewed had evidence of direct instructions from the client. The remaining few included initial instructions from a CMC, but these were followed up with the client.

Collecting information

- Firms collected a variety of information before making a claim. The most common information gathered at the outset was the client's account details.

- A number of firms asked clients to fill out a Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) PPI questionnaire, or asked for the information to fill it out for them.

- Firms reported that larger numbers of clients were now coming forward who did not know whether they had purchased PPI, let alone whether it was mis-sold.

Case progression

- Firms reported low success rates, but this seems to be due to the number of cases where the client did not know whether they had PPI.

- Most files we saw (41 out of 60) contained letters of claim that had been tailored to the client's circumstances in some way, but 18 seemed to be in a wholly standard form. The lender in the remaining file paid redress without a letter of claim being sent.

- Four out of 60 files we reviewed had letters of claim that included contradictory heads of claim. While this is a small proportion, it is still too high.

- Most claims in the files we reviewed took six months or less to resolve.

- Once clients with no PPI and duplicate claims were excluded, the success rate improved.

Fees and value

- Fees were the major issue we encountered. Only three firms were unaware of our 2017 warning notice when we visited, one of which was a visit on the day of publication.

- Only two firms charged 15 percent or less, as set out in our 2017 warning notice.

- Fees ranged from 10 percent plus VAT to 50 percent plus VAT. Often the fees we saw on files could be higher or lower than firms' standard rates.

- We expect all firms to immediately consider their fee arrangements in light of our warning notice and the impending fee cap. If firms are unable to demonstrate that they are acting in the best interest of their clients, then we will consider the need to take regulatory action.

- All firms used damages-based agreements.

- Lenders tend to pay redress direct to the client, unless the claim was litigated. This could create problems if the client was unaware that the fees had not been deducted, or were unwilling to pay.

- Firms said they avoided taking on clients who were in arrears with lenders, as their redress would be offset against the remaining debt. It would not be in the client or firm's best interest for this to happen, as the client would not receive cash redress but would still owe the firm its fee.

Litigation

- Litigation was undertaken in a minority of cases, though it is increasing over time.

- The majority of such cases settle before reaching a hearing.

- Clients were made aware of the risks of litigation, and firms made sure they had specific client authority to issue proceedings.

Alternative business structures (ABSs)

- Concerns about CMCs converting into ABSs to avoid FCA regulation seem to be unfounded. We found that only a very small number of firms have taken this step and only two such firms were in our sample.

- Only one ABS shared information with a related company, and did so after gaining client consent. They had numerous safeguards to prevent unauthorised access to client data.

Insolvency work

- In most insolvency cases, the client was not the PPI policy holder but an insolvency practitioner seeking to maximise returns on their assets for the benefit of all creditors. This fundamentally changed the nature of the case.

- Firms that specialised in insolvency often made speculative claims. This was because they acted for insolvency practitioners rather than PPI policy holders, and may have had difficulty in getting information.

- Firms specialising in insolvency work kept the policy holder informed of what was happening. Making contact in this way helped them if the lender needed any further information or evidence.

- Offset of redress is more common in insolvency cases, but firms were more experienced in challenging it.

Training and supervision

- Most fee earners had received training on PPI matters within the last six months.

- Four fee earners, for various reasons, had never received any PPI training.

- All fee earners had clear lines of supervision.

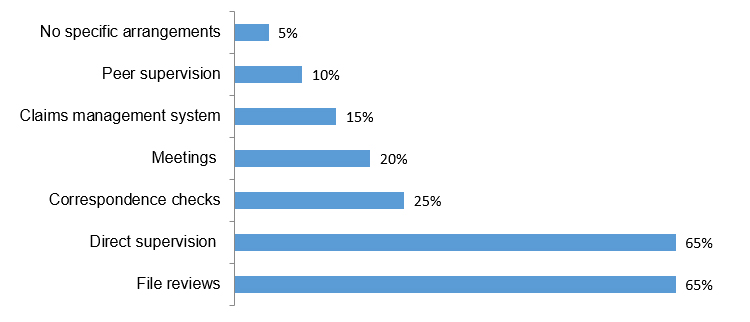

- Most firms supervised through file reviews, though these varied in regularity. An equal number of firms used direct supervision.

Engagement

During this thematic review, we have engaged with both firms and lenders. These lenders were high street banks and credit card providers.

Firm engagement

Our firm engagement took place in August to October 2017 and involved contacting a sample of 20 firms that have conducted PPI work. We then gathered information in three stages:

- a mainly quantitative online questionnaire completed by firms

- an interview with the manager or managers primarily responsible for handling PPI work

- an interview with a PPI fee earner, including a review of three of their files.

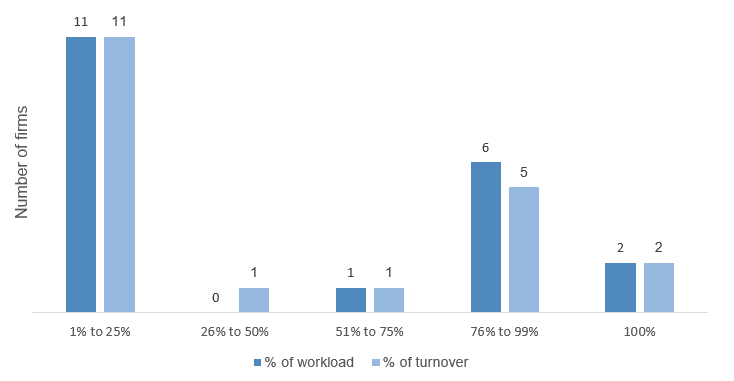

The firms were a mixture of sizes and corporate structures. Two had entered the sector within the last 12 months, while others were in the process of leaving it. Some specialised in PPI work, whereas others were traditional firms who offered it among a range of other services. Eight firms were ABSs.

Engagement with lenders

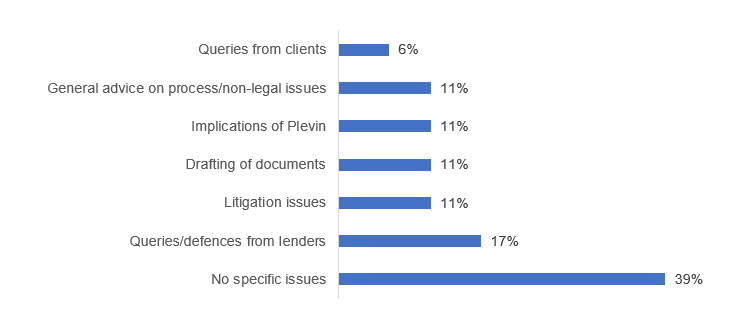

We also engaged with a variety of lenders, who told us about their experiences with solicitors making PPI claims. This was through both individual engagement and attending regular forums on PPI matters. Lenders told us that solicitors represented a small percentage of the PPI claims they received, but that they naturally represented nearly all claims that were litigated. Lenders shared some of their concerns about regulated firms, including:

- firms requesting large volumes of information via data subject access requests (DSARs)

- firms being, in their view, too ready to litigate

- firms submitting large numbers of pro forma complaints that did not present any specific reason why the client thought the PPI had been mis-sold.

Some of the above may, depending on the circumstances, be appropriate courses of action for a firm to take. Firms should, though, remember that a PPI client is entitled to the same level of client care and personal service as a client in any other field of law. Although PPI can be a very process-driven area, firms should not lose sight of the fact that at the centre of each valid claim is a client who has been unfairly disadvantaged.

Given that both lenders and firms have a shared objective in getting a fair outcome for the PPI customer, we asked lenders for their thoughts on what firms could do to make the PPI process quicker and more efficient. Some lenders jointly gave us their views in the form of a guidance note, which is attached at Annex C. It highlights several practices of concern, including:

- litigation being pursued prematurely

- claims being received in identical terms and not tailored to individual clients

- firms failing to undertake basic checks as to whether a client had PPI before submitting a claim or had already received redress from the lender

- firms submitting defective or unclear DSARs.

We attach this note with the consent of the lenders involved, so that firms can consider its contents in light of their own practices. Whether the views expressed in this note reflect our own will depend on the circumstances of any individual case.

New clients

Key findings of the thematic review

- The majority of firms took care to tell clients that they could make a claim for themselves.

- Firms told us that they largely relied on referral/introducer arrangements with CMCs (60 percent) and online advertising (50 percent).

- One firm admitted that it had historically cold-called clients, but no evidence of cold-calling was found apart from this. This is a serious issue, and we will always take appropriate action when we find evidence of this.

- The vast majority of files we reviewed had evidence of direct instructions from the client. The remaining few included initial instructions from a CMC, but these were followed up with the client.

Taking on new clients is an important exercise for clients and firms. It helps clients understand the process and the work that is being carried out on their behalf. At the outset, clients should also receive information about how much the work will cost. An informed client is able to make decisions about what steps they should take and whether they need legal assistance.

A thorough process for taking on new clients also helps a firm provide better advice to clients. These activities are particularly important because we ask firms to act in the best interests of each client 2 and to provide a proper standard of service to their clients 3.

Our 2012 guidance note and 2017 warning notice mentioned a number of our concerns in this area:

- Firms must show that clients have made an informed decision, having considered the options available. This may include firms discussing the possibility of clients. themselves making the claim, and whether the firm's involvement justifies the costs.

- PPI claims must be made with the knowledge of the policy holder.

- Firms must understand why their clients have instructed them. We have received reports that firms, like CMCs, are using direct marketing techniques to recruit clients, in breach of outcome 8.3 of the SRA Code of Conduct 2011. Out of the complaints we have received about PPI work in the last three years, one-third involved some form of direct marketing by phone or post. Clients should be aware of how their information could be used, particularly where information has come to the firm indirectly. Cold-calling is serious misconduct, and we take action when we find evidence of it.

- Firms must be satisfied that clients need help. We have received reports from lenders about firms sending speculative claims to them.

The PPI claims process is intended to be simple and individuals are encouraged to make claims themselves by lenders and the government. It is a free process and people can get impartial advice about how to make a claim from various consumer organisations.

We expect firms to be open and transparent about this to prospective clients. Ultimately, firms must consider whether it is in the client's best interests to charge them for non-legal work that the client can do themselves for free.

Communication on how to make a claim

During our visits, we explored how transparent firms were on this issue. Seventeen firms told us that they make clients aware that they can make a claim themselves. Firms said they told clients in a variety of ways:

- 16 firms informed clients in writing, generally as part of their client care documentation

- five firms informed clients both in writing and verbally

- one firm informed clients only verbally.

Three firms said they did not provide information to clients about making a PPI claim themselves because:

- clients approached the firm after their own research and chose whether to instruct the firm

- the firm only dealt with:

- Plevin cases, which the firm felt were claims generally unsuitable for clients to make themselves

- cases where the clients have already made an unsuccessful attempt to recover redress themselves

- the claims were referred by an introducer, which the firm understood to have already advised the client that they themselves could make a claim.

Even in these circumstances, we consider that clients should be told by the firm about the possibility of making a claim themselves.

Of the 60 files we reviewed:

- 41 files showed that the client was informed that they could make a claim themselves

- 11 had no evidence

- it was unclear on the remaining eight files whether this information was given (for example, it was said to have been done verbally, although this was not recorded).

Although firms need to consider the facts and circumstances of each PPI claim, we expect that, in most cases, firms will tell a client that they can make a PPI claim themselves. If this is done verbally, it should be confirmed in writing to the client.

Attracting clients

We expect firms to interact with clients in an open and transparent way. Firms should act with integrity 4 and behave in a way that maintains the trust that the public place in the legal profession 5. These requirements are particularly relevant when firms are trying to generate work.

Our 2012 guidance note reminded firms of their obligation to make sure that their publicity was accurate. When advertising, we expect firms to be clear and transparent.

In particular, firms should not suggest that they can get a better outcome for clients unless they have evidence to back this up. Firms are also prohibited from making unsolicited approaches to members of the public 6 or allowing others to do so on their behalf 7.

At the time of our visit, we found that firms met the minimum standards that we expect. However, one of the firms had historically cold-called prospective clients. This is a serious issue, and one we will always act on when we find it.

Another firm had a paragraph on their website which informed clients that they could make a claim for themselves, but suggested it was an overly long and complex process. We drew their attention to our 2012 guidance note and also an Advertising Standards Authority ruling relating to a CMC on the same subject 8. They agreed to change the paragraph and provided evidence when they had done so.

Firms told us that they largely relied on referral/introducer arrangements with CMCs (60 percent) and online advertising (50 percent). This information was reflected by the files we saw, with much of the work originating from introducers/referrers (78 percent) and online advertising (18 percent).

The types of online advertising varied. While some firms had set up specific websites to channel enquiries, others placed adverts on third party websites. Firms had used online advertising with varying degrees of success. One firm considered that its PPI venture had been a success due to its online presence. In contrast, another business's dedicated PPI website yielded very poor results and few clients. They had abandoned the website as a poor investment.

CMCs and responsible sourcing of clients

There are many CMCs operating within the PPI market. CMCs are commercial businesses that process claims for compensation in return for a fee. Any business in England and Wales that carries out this work must be authorised by the MoJ's Claims Management Regulation Unit. While CMCs generally carry out PPI work themselves, some will refer cases to regulated firms. A few firms told us that CMCs sent them cases that had already been rejected by the lender.

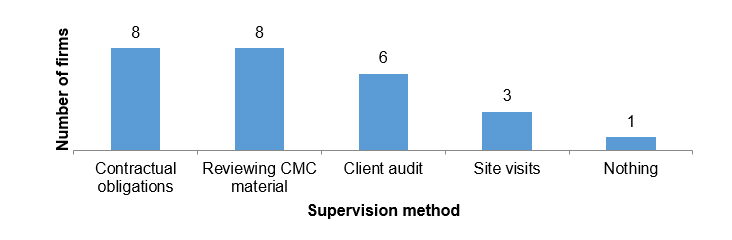

If a firm uses a CMC, the firm must be satisfied about how the clients have been sourced. Twelve firms within our sample used CMCs and all but one of the firms carried out checks to make sure they were acting responsibly. Most firms used more than one method:

Firms often used a number of these options in tandem and this is important. While contractual clauses may help define the nature of the relationship between a firm and a CMC, the firm should take steps to check compliance with the agreement. We consider that the most effective checks are invasive and random.

Where a third party, such as a CMC, is involved in a claim, firms must confirm who their client is and what work they need. Some firms said that they did not believe client due diligence was necessary, as PPI work falls outside the scope of anti-money laundering regulation. Firms should not see this as a narrowly defined money laundering issue. Our 2017 warning notice states that firms must not take unfair advantage of third parties 9. This includes making demands on behalf of a client that are not legally recoverable 10. To make a claim, firms should check they have the correct details of the client's identity.

We found that all the firms took steps to check that they were acting on behalf of their client. Most firms told us that they spoke directly with their client (18) but some relied on letters of authority and written correspondence (2). This was reflected in the 60 files we reviewed:

- 52 files contained clear evidence of instructions from the client

- eight files contained initial instructions from a third party, such as a CMC. In each case, the firms subsequently confirmed the instructions with the client.

We also asked firms whether they met PPI clients in person, and 11 firms said that they had:

- eight firms saw 1 percent of their clients

- two firms saw 10 percent of their clients

- one firm saw 90 percent of their clients.

Although these percentages are small, we were still surprised because all the firms operated on a national basis, with clients from all over the country. Larger percentages were recorded by firms who litigate matters for clients.

Good practices

- Telling clients about the possibility of making the claim for themselves, that it is straightforward to do so, and that various sources of free help are available.

- Providing comprehensive information about the process and anticipated costs to the client in a language that they understand.

- Clearly informing clients that they can make a claim themselves.

- Reviewing CMC publicity and processes to confirm compliance with the Principles and Outcomes of the SRA Handbook 2011.

- Conducting invasive and random audits of CMCs.

- Gathering client ID and confirming each client's instructions.

Poor practices

- Publicity containing misleading information, eg about success rates or complexity of the claims process.

- Cold-calling prospective clients.

- Failing to gather evidence of the client's identity and therefore verify them.

- Being unable to show how a client arrived at the firm.

Collecting information

Key findings of the thematic review

- Firms collected a variety of information before making a claim. The most common information gathered at the outset was the client's account details.

- A number of firms asked clients to fill out a Financial Ombudsman Service (FOS) PPI questionnaire, or asked for the information to fill it out for them.

- Firms reported that larger numbers of clients were now coming forward who did not know whether they had purchased PPI, let alone whether it was mis-sold.

Firms must gather relevant information from their clients about whether they purchased PPI and whether it was mis-sold. We have heard reports of firms making speculative claims to lenders.

The 2017 warning notice states that when taking instructions from a client, firms must:

- make sure they have the correct details of the client's identity and claim

- not submit claims unless there is evidence of a sound basis for the claim and valid instructions

- not demand anything from a third party, such as compensation for mis-selling, where there is no legal right to recovery.

Failure to do this may be a breach of the following SRA Principles:

- Principle 1, upholding the law and the proper administration of justice

- Principle 2, acting with integrity

- Principle 3, maintaining public trust in the profession.

Failure to properly assess claimants and claims may also leave both firms and clients open to allegations of fraud. We asked firms about the information they gather from clients and reviewed their files to understand how firms assess whether their clients have grounds for a claim.

Types of information

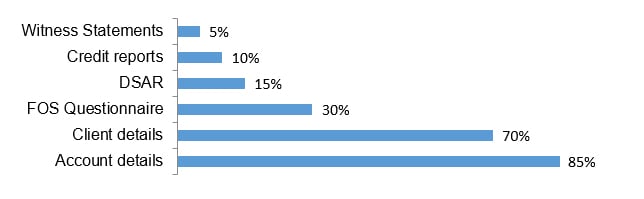

The firms gathered a range of information:

All firms told us they would gather basic information, such as account numbers and client details. Two firms reported that this was the only information they requested. Others would ask for information about their circumstances and reasons about why they believed PPI was mis-sold. In some cases, this might be through a conversation with the client. Others used standard questionnaires, which often replicate FOS's questionnaire, which are sent out to clients to complete and return. In addition to account information, these questionnaires are designed to gather information about the circumstances in which PPI was sold and the clients' circumstances at that time. FOS's questionnaire is freely available to the public via its website and is designed to help consumers to make complaints about PPI themselves.

Some firms called all clients to ask further questions or complete a questionnaire, which was very similar to the FOS's questionnaire. One firm had a set script of information to collect, for example loan agreements and bank account numbers. The firm also went through a PPI questionnaire with the client to see if PPI was mis-sold. Once the questionnaire was completed, the firm sent it to the client to check and sign and return with the evidence. Other firms would rely on the information provided by clients or on the client completing the questionnaire and sending it back.

Having a direct conversation with the client about their PPI claim is the standard of service we expect from firms. This helps make sure that the firm are aware of and understand each client's individual circumstances that led to PPI being taken out. This will better inform the firm about the client's claim as it progresses and, in particular, the letter of claim to the lender. It will also help if the claim is referred to FOS or if proceedings are issued.

Once the initial information was provided, firms would generally send a client care pack to the client. Although the contents of the pack varied between firms, it usually included a client care letter, terms of business and letter of authority. Some firms also included an explanation of the PPI claims process through a leaflet or factsheet, a helpful practice which can assist in managing client expectations. The pack would also usually include a DBA, also known as a contingency fee agreement, for the client to sign.

Firms then assessed the information provided by the client/lender to see if there was a valid claim. If there was insufficient information or no prospects of success, the claim ended. It may be helpful for firms to gather information in a structured way that is familiar to lenders. However, if there is no further analysis of the information and the form is simply forwarded on to the lender, it is unclear what value the firm is adding.

Type of information held on file

In the 60 files that we reviewed, we found the following information had been collected from clients at the outset of the claim:

| Type of information held on file | Number of files with this information |

|---|---|

| Account numbers | 46 |

| Reason why PPI was thought to have been mis-sold | 28 |

| PPI policy numbers | 9 |

| Amount client had paid in PPI | 6 |

We heard that, often, clients do not have detailed information about their PPI policy or indeed know whether they ever had one. They may not remember the circumstances in which it was sold. This may be due to the passage of time and not having retained the relevant information. Firms reported that there had been a recent rise in the numbers of clients who did not know if they had PPI.

Some firms use DSARs to gather information from the lenders about their clients. Everyone is entitled to make such a request. It may help to gather information that was otherwise not available and therefore make sure that only claims with justifiable grounds are submitted. Some firms told us that DSARs are useful where the lender who sold the PPI has been taken over by another lender. In these situations, the current lender does not always have access to the previous lender's legacy systems. Lenders confirmed that this was the case, and where this happened they would generally respond that they could not locate a history of the PPI policy.

Firms should, however, consider whether a DSAR is the best method for gathering information. It should also be made in a form that clearly identifies it as a DSAR and include the statutory £10 payment. Lenders told us that they often encounter DSARs that are not treated as such due to procedural defects, such as failing to include the statutory fee.

Where firms are litigating cases, they told us they gather as much information from their clients as possible. For example, in addition to completed questionnaires and DSARs, one firm gathered witness statements from both their client and the lender.

Good practices

- Gathering information from the client at the outset to ascertain whether there are grounds for a claim before contacting the lender.

- Using the information provided by the client to draft claims tailored to the specific case.

- Only taking on cases where there is sufficient information to make a valid claim.

Poor practices

- Not gathering information from clients to assess whether there are grounds for a claim.

- Relying solely on basic information from clients as the basis for a claim.

- Failing to use information provided by clients to tailor claims appropriately.

Case progression

Key findings of the thematic review

- Firms reported low success rates, but this seems to be due to the number of cases where the client did not know whether they had PPI.

- Most files we saw (41 out of 60) contained letters of claim that had been tailored to the client's circumstances in some way, but 18 seemed to be in a wholly standard form. The lender in the remaining file paid redress without a letter of claim being sent.

- Four out of 60 files we reviewed had letters of claim that included contradictory heads of claim. While this is a small proportion, it is still too high.

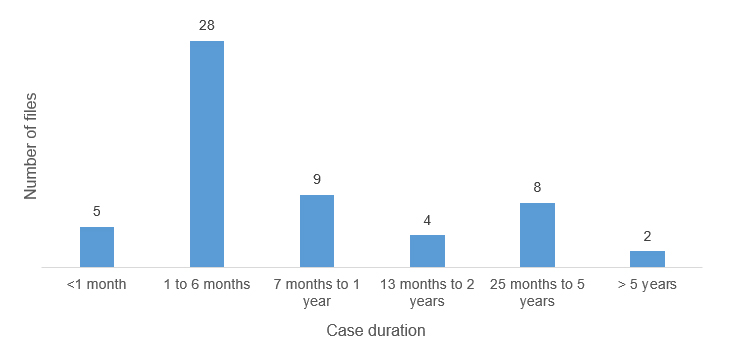

- Most claims in the files we reviewed took six months or less to resolve.

- Once clients with no PPI and duplicate claims were excluded, the success rate improved.

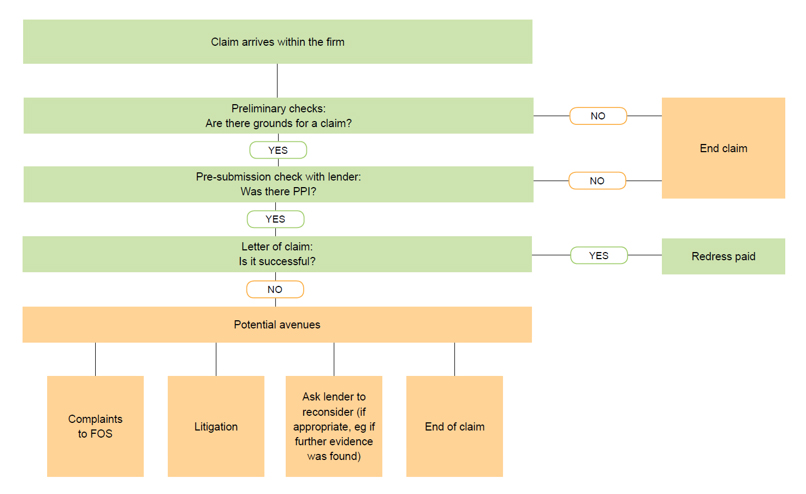

Progression of PPI cases

The chart below shows the stages a PPI claim may have.

Our 2012 guidance note states that firms must:

- make sure that the service provided is of a proper standard

- act in the best interests of their clients

- consider whether any correspondence they send is clear, appropriate in the particular circumstances and provides the information the recipient needs to deal with the claim.

Preliminary checks

The most fundamental check that needs to take place is whether the client had PPI. Firms said that, in recent months, the number of clients who did not know if they had PPI had increased. This was attributed to increased awareness following the announcement of a deadline and an FCA advertising campaign.

Firms initially analyse the claim to see if there was enough information provided to form the basis of a PPI claim. If there was not, firms might:

- make a DSAR to obtain further information and confirm whether PPI was in place

- use lenders' pre-submission processes to get further information. This involves a basic check as to whether the client had PPI or indeed any financial product with the lender.

Lenders' pre-submission processes are advertised as a free PPI check and are available to members of the public as a free service. Given the increase in clients wanting to check if they were mis-sold PPI policies, or indeed held one at all, the volume of claims rejected due to there being no PPI are high. This is not surprising and this sort of filtering is how pre-submission should function. Some firms said that clients would occasionally dispute that there was no PPI, and, in these cases, they would ask the clients for evidence before going back to the lender. Equally, other firms said that taking referrals from CMCs meant that PPI had already been established, removing this issue.

Some of the firms we visited sent information requests directly to lenders and in a format the lenders wanted. One firm we visited had different service level agreements with different lenders and sent information requests on a daily basis, at the lender's request, to avoid dropping large numbers of information requests at one time.

If there was the basis for a PPI claim, firms progressed them in a variety of ways including:

- a head of team reviewing and risk assessing all PPI claims before passing them on to fee earners, who then worked under their supervision

- having an automated system, for example using case management systems to progress cases, generate letters and provide clients with updates

- having separate teams to deal with each part of the PPI claim including evidence gathering, drafting the letter of complaint and dealing with redress (for example checking the suitability of the offer and the acceptance process).

One firm we visited had two teams dealing with PPI claims. The administration team signed up the client and sent out all relevant paperwork, for example the client care letter, the DBA and letter of authority. This team also screened out any clients in individual voluntary arrangements 11 (IVAs), bankrupt clients and poor PPI claims. Claims were then entered onto the firm's system and passed to a second team which produced a letter of claim to the bank and deal with it as it progressed.

Letters of claim

If the firm takes the claim forward based on the information provided, a letter of claim is sent to the lender. There must be a proper legal basis for sending the letter of claim. Lenders have expressed concern about the numbers of PPI claims they are rejecting after receiving a letter of claim where there was no PPI in place. Although there may be issues with information held by lenders, firms must make sure that they have taken all necessary steps to properly establish whether there was a PPI claim. They can do this by:

- making enquiries with the lender

- speaking to their client

- collecting all available information and documentation from the client in advance of a letter of claim being sent.

When sent, letters of claim tended to be in a standard format tailored to the client's circumstances, or followed the standard PPI questionnaire provided by FOS.

Our file reviews specifically looked at whether the claims submitted by firms on behalf of clients were clear and tailored to the client's circumstances.

Of the 60 files we reviewed:

- 41 contained letters of claim, which were clear and tailored to the client's circumstances

- 18 contained letters of claim in a standard format, which was not adapted to the client

- one was a file where the lender paid compensation immediately after an initial enquiry, rather than a letter of claim.

We would draw a distinction between standard wording and standard letters. Standard wording, where the firm uses precedent wording which it has found to be effective and can be adapted to the client's needs and circumstances, are common in other areas of legal work and can be an efficient way of making a claim. Standard letters, where identical wording is used and only client details are changed, do not represent a good standard of service.

We expect firms to always act in the best interests of each client by making sure that all letters of claim address the individual needs and circumstances of each client, rather than rely on standard letters. One firm we visited took the view that, since Plevin, all PPI where commission was paid is inherently unfair, and this meant it could use generic documentation. Whether or not this is the case, client cases still need to be assessed individually and on their merits.

On four files, the heads of claim were contradictory. This was because the letters of claim were in a standard form and listed a wide variety of heads of claim, for example asserting in one place that PPI was not discussed at all and in another that the discussion had been inadequate.

Such letters raised these issues for the firm:

- failing to provide a good standard of service to clients

- being very unlikely to be able to justify anything more than minimal fees

- potentially making a false representation.

At one firm, the reason given for contradictory letters of claim was because the firm had streamlined its PPI process, giving rise to a data issue, which meant that the appropriate precedent wording for the particular circumstances of each client were not being selected. The firm confirmed that they would immediately address this issue.

If the lender refuses the claim, the matter is assessed again by the firm and further information/clarification may be sought from the client (for example circumstances of employment). If the further information/clarification shows that there is still a valid claim, the matter is either referred back to the lender, to FOS or litigated.

Length of a PPI claim

The length of time to conclude PPI claims varied for a number of reasons, including that the claim:

- went through the FOS process, and timeframes vary

- had been stayed until further guidance/advice was received on Plevin cases

- was litigated.

Our files review showed a similar pattern and confirmed there was no typical average length for a PPI claim. The range of time for a case varied from within a month to many multiples of that. Of the 60 files we reviewed, 56 had concluded. As the chart below shows, more than half had concluded within six months or less.

Cases that took more than one year tended to be stayed Plevin cases and cases referred to FOS, reflecting what we had been told.

Rejection

Lenders reported that a considerable number of claims were rejected. Some common reasons were:

- the client did not hold PPI

- the client had not held any financial product with the lender

- the claim was a duplicate of one already resolved.

Once this hurdle had been passed, the rate of upheld complaints was high, though a minority were still rejected as not having been mis-sold.

It is worth noting that a claim not being upheld does not mean that it was not legitimately made, based on the evidence available at that time to the firm. Nonetheless, a firm facing a high percentage of rejections from a particular lender should consider why this may be, and what steps can be taken to improve this. We consider that firms should respond to this by building good working relationships with lenders and trying to understand their circumstances and processes.

We also asked firms to give us an estimate of their own success rates. Many firms initially gave us figures which seemed very small, around 10 to 20 percent. We found that this was because they tended to take into account claims where, after initial contact, the client was found not to have had any PPI, or indeed not had any product with the lender.

We therefore asked them to provide the number of PPI cases submitted to lenders for the year to date (January to October 2017). As expected, this showed that a significant number of claims are rejected due to no PPI/relationship with lender, while a smaller number are deemed not to have been mis-sold.

Type of claim

| Type of claim | Totals |

|---|---|

| Total number of claims submitted to lenders in 2017 to date | 50,071 |

| Claims rejected by lenders due to no PPI and/or no relationship with lender | 13,887 |

| Claims rejected by lenders as not mis-sold | 5,071 |

Nearly one-third of the total claims submitted by sample firms this year were rejected due to no PPI being present. A further 10 percent were rejected as not mis-sold. Again, these claims are not necessarily invalid. The figures also do not take into account claims awaiting a decision at the time the data was collected.

Firms should, however, make sure that:

- they use lenders' pre-submission processes effectively, to filter out at an early stage any cases that cannot progress

- complaints are only submitted where there are proper supporting grounds, or where reasonable efforts to establish the position have been exhausted.

Good practices

- Giving clients a written explanation of the PPI process, possibly through a leaflet or factsheet.

- Speaking to all clients personally and discussing and recording further information about the circumstances around the client taking out PPI.

- Collecting all relevant documentation from the client.

- Analysing and discussing with the client all reasons for refusal by the lender. Where appropriate, further information and evidence is gathered.

- Dividing cases into stages (for example new clients, case progression, redress), with fee earners having specific responsibility for a stage and being supervised at each stage.

- Discussing letters of claim with clients, tailoring them to reflect the client's individual circumstances and getting approval from the client before sending it to the lender.

Poor practice

- Failing to contact clients to discuss individual circumstances relating to the PPI claim.

- Producing letters of claim that were not tailored to the client's specific circumstances and no detailed facts were sought.

- Submitting letters of claim with contradictory heads of claim.

Fees and value

Key findings of the thematic review

- Fees were the major issue we encountered. Only three firms were unaware of our 2017 warning notice when we visited, one of which was a visit on the day of publication.

- only two firms charged 15 percent or less, as set out in our 2017 warning notice. They offered a range of justifications for this.

- Fees ranged from 10 percent plus VAT to 50 percent plus VAT. Often the fees we saw on files could be higher or lower than firms' standard rates.

- We expect all firms to immediately consider their fee arrangements in light of our warning notice and the impending fee cap. If firms are unable to demonstrate that they are acting in the best interest of their clients, then we will consider the need to take regulatory action.

- All firms used damages-based agreements (DBAs) 12.

- Lenders tend to pay redress direct to the client, unless the claim was litigated. This could create problems if the client was unaware that the fees had not been deducted, or were unwilling to pay.

- Firms said they avoided taking on clients who were in arrears with lenders, as their redress would be offset against the remaining debt. It would not be in the client or firm's best interest for this to happen, as the client would not receive cash redress but would still owe the firm its fee.

Cap on redress

The Financial Guidance and Claims Bill will impose a fee cap of 20 percent plus VAT in PPI claims, to be policed by relevant regulators. This is to take effect two months after the Financial Guidance and Claims Bill receives royal assent 13. At the time of writing, precise timescales for this have yet to be made public. This section deals with the situation as at the time of writing, until any legislation imposing a cap comes into force.

At present, the issue is addressed in our 2017 warning notice. This states that we will consider any fee over 15 percent to be unreasonable, unless the work and the risk involved justified a greater percent of the redress. This figure mirrors that in an MoJ consultation launched in February 2016.

Although our 2017 warning notice will continue to apply to fees until the government cap is in place, we expect firms to treat clients fairly by:

- making them aware of the imminent cap

- explaining why the firm proposes to charge more.

Clients should be in a position to make an informed choice as to whether they should start their claim immediately, or wait for the cap. We expect all firms to immediately consider their fee arrangements in light of our warning notice and the impending fee cap. If firms are unable to demonstrate that they are acting in the best interest of their clients, then we will consider the need to take regulatory action.

How do firms charge clients?

All the firms we visited used DBAs in PPI matters to some extent. These are contracts where the client will only pay solicitors' fees if the case is successful, and the fee is a fixed percentage of the amount of redress recovered. This allows the risk to be shared between the firm and the client.

An inherent feature of DBAs is that when the client signs the retainer they do not know how much their claim will eventually be valued at. This in turn means that they do not know how much the firms' fees will be. This is particularly true in PPI cases, where even the existence of a policy may not be known until the firm has contacted the lender on the client's behalf. PPI redress can be for significant amounts: the highest amount we saw in file reviews was £25,418.95. It is our view that a firm's fees should be proportionate to the work and risk taken on by the firm.

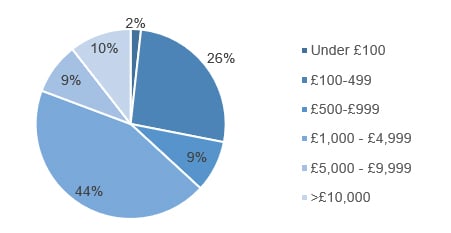

Of the 60 files we reviewed, 57 had concluded with payment of redress. The remaining three were in progress as the firm was new and had not at that time concluded any claims. The largest amount of redress we saw was more than £25,000, while the smallest was just over £15.00. The average redress on these 57 files was £3,577.94. The chart below shows that the largest proportion of files involved gross redress (ie before fees and disbursements were deducted) of £1,000 to £4,999.

As noted above, the vast majority of firms in the sample had seen the 2017 warning notice before we visited. Despite this, we found the following fees being charged as a percentage of redress 14:

| Percent of redress charged | Total deductions including VAT | Number of firms |

|---|---|---|

| 10%+ VAT | 12% | 1 |

| 15%+ VAT | 18% | 1 |

| 20% inc VAT | 20% | 1 |

| 25% inc VAT | 25% | 1 |

| 25%+ VAT | 30% | 7 |

| 28%+ VAT | 35% | 1 |

| 30% + VAT | 36% | 4 |

| 35%+ VAT | 42% | 1 |

| 40% inc VAT | 40% | 1 |

| 50% inc VAT | 50% | 2 |

One firm that had historically charged 25 percent plus VAT was in the process of reducing this to 15 percent plus VAT. They told us that this was due to the 2017 warning notice, and it was going to finish their current cases and close their PPI department. It said that it did not think the work would be profitable at 15 percent, and it did not want to have to justify charging more. As already stated, we expect firms to adhere to the warning notice and take action in advance of the proposed fee cap so that they can demonstrate they are acting in best interest of their clients. On several occasions, the files we examined had a different fee rate to what the manager had told us. One firm at first told us that they charged 25 percent plus VAT, but the files we examined were two at 30 percent plus VAT and one at 50 percent plus VAT, the highest fee we encountered. Firms may agree individual fees with clients, but they should make sure that:

- the rates are comparable to the firm's hourly billing rate

- it does not contradict any rates advertised to potential clients

- clients are treated fairly in billing for similar cases.

In the files we reviewed, the fee charged matched that in the client care letter in all but three matters. Those matters related to an insolvency specialist, whose IP clients had agreed the percentages at a creditors' meeting.

Firms also differed as to whether the £10 fee for a DSAR, where used, was included in their own fees. Some would charge this to the client as a disbursement.

Adding value to the client's claim

As the 2017 warning notice states, 15 percent of the redress is not an absolute ceiling, and firms may charge more if the work and risk justify it. We asked firms to tell us the basis of their fee rate, and how they thought that the work they did justified the fee.

Some of the firms were able to give convincing justifications for their charging rates:

- Performing time-consuming and complex calculations of PPI and commission rates, including periods of renegotiation and compound interest. In one case, this had led to a lender's initial offer of £83.00 being increased to an eventual award of £14,400.

- Dealing with more complex matters, such as claims against the Financial Services Compensation Scheme.

One firm who specialised in insolvency work told us that using a solicitor is generally more cost effective for the insolvent person, as an insolvency practitioner would take longer and therefore charge more.

Some firms also said that they litigated cases after claims had been turned down by the lender. They pointed out that clients were not generally expected to carry out litigation themselves. While litigation may be appropriate in certain circumstances, firms should consider the guidelines as set out in Andrew & Ors v Barclays Bank Plc 15. Among other things, these state that litigation should only be considered when a claim has been rejected by the lender or the lender has failed to respond in time.

We were also told that litigation was often necessary in Plevin claims as lenders would not disclose the rate of commission without a court order, citing commercial sensitivity. We asked lenders about this, which confirmed that this had been the case until the 2017 FCA guidelines came into force, but since then they had been disclosing commission rates.

Other firms gave less justifiable answers, and we do not necessarily consider the following to justify charging more than 15 percent:

- saving clients time

- performing a service in terms of carrying out a task that clients do not want to do themselves

- references to experience in dealing with PPI claims

- the work would not be profitable otherwise.

Time saving was commonly given as a justification. One manager compared his services to a decorator – most people can paint a room competently, but some choose to pay someone else to do it to save time and inconvenience. The comparison may be a valid one, but it does not necessarily justify charging more than 15 percent.

It also follows that the higher the rate charged by firms, the more they would need to justify that charge. For example, if a firm is charging 50 percent including VAT, we would expect to see evidence of a large volume of necessary and complex work that clients could not reasonably be expected to do themselves.

A few firms also claimed to be able to obtain a better result than clients would get if they pursued claims themselves. This may or may not be the case, but firms should make sure that they have the evidence to back up such claims. Further guidance can be found in our 2012 guidance note.

One firm charged clients an administrative fee for review of client documents and entering them on the firm's system. We are also aware of another firm charging a similar administrative fee on completion of the case. If firms wish to do this, they must make sure that they treat clients fairly. This includes bringing the additional fee to the client's attention before they sign the retainer, and making sure that the fee is representative of the work done. Purely administrative tasks, such as transferring funds or data entry, should form part of the firm's overheads and should not be charged to the client.

In the case of four firms, the basis of the fee charged to clients would change if the matter went to litigation. These all involved moving to a conditional fee agreement (CFA). Under a CFA, the firm would charge an hourly rate payable by the other side if the case was successful. In addition, the firm would charge a success fee, which was a percentage of the redress gained. The firms which gave figures said that this percentage would be the same as in the DBA.

In all but two of the 60 files we reviewed, the basis of charging was clearly explained to the client. In the remaining cases, the files were handled by a firm that acted for insolvency practitioners and the basis of charging had been dealt with in a separate document. Firms generally explained their charges in:

- client care letters

- terms of business

- DBA agreements.

In addition, one firm provided a helpful explanatory leaflet to clients, which summarised the general points of a PPI case. Notably, the leaflet included examples showing how much would be deducted from certain given figures. This helps to treat clients fairly by managing their expectations.

How is redress paid to clients?

We found from our file reviews that the lender will generally pay redress directly to the client, rather than the firm's client account. This means that firms will then need to ask the client for their fees. The exception is where the claim has been litigated.

As might be expected, clients sometimes resisted paying the firm its fee. Two of the firms we spoke to reported similar situations where clients received redress direct from the lender, then cancelled their retainer before the firm was notified. This was an attempt to avoid paying the firm's fee. Firms also said that clients did not always realise that the firm's fees had not already been deducted when they received the redress, and promptly spent it. Where this happened, the firms tended to agree a payment plan with the client, allowing them to repay the fees over time.

While this can be a difficult situation for the firm to resolve, it is an inherent risk of the sector. It will not in itself be sufficient to justify charging high percentages.

What if a client is in arrears?

If a client's debt to the lender still exists and they are in arrears, the lender may opt to offset the PPI redress against the amount still owing 16. This can create a difficult situation if the client has instructed a firm, as the client will still owe the firm its fees but will not have the cash from the redress to pay them.

A number of firms told us that they try to avoid taking on such clients, advising them that it would not be in their best interests to enter into a DBA. They also said that, occasionally clients will, intentionally or not, fail to mention arrears. Some firms said they would try to agree a payment plan, but the majority said they would write the fees off.

The majority of firms, 80 percent, made clients aware of the risks of offsetting before accepting the retainer. Nine firms did so in their initial documentation, for example in their client care letter or terms of business.

One of the remaining four firms did not do so because they acted for insolvency practitioners, who were already aware of the risks. Another firm said it would not take on such cases, so saw no reason to raise it. It mistakenly thought that offsetting only applied to IVAs and bankruptcies. In reality, it can apply whenever a client is in arrears. Firms should be aware of the risk to clients and warn them accordingly.

Good practices

- Comparing the cost of a PPI DBA to the firm's hourly rate, and checking that they are proportionate.

- Giving clear and concise costs information to clients at the outset of the case.

- Quoting fees inclusive of VAT, so that the total deductions will be easier to understand.

- Being able to evidence justification for any fees above the 15 percent stated within our warning notice.

- Finding out whether the client is in arrears and explaining the potential impact to each client.

- Explaining to each client that, if redress is paid to them, they will need to set aside a percentage to pay the firm.

Poor practices

- Failing to check whether the percentage claimed by the firm is proportionate to the work done.

- Charging extra for administrative and other fees without justification.

- Failing to warn clients of the risk of their fees being offset.

Litigation

Key findings of the thematic review

- Litigation was undertaken in a minority of cases, though it is increasing over time.

- The majority of such cases settle before reaching a hearing.

- Clients were made aware of the risks of litigation, and firms made sure they had specific client authority to issue proceedings.

If the client wishes to continue with a claim after a lender has rejected it, they have the choice to:

- make a claim through FOS

- litigate the claim through the court process.

Litigation is an area where solicitors can potentially show that they are adding value to the client's claim. As a reserved legal activity 17, it is something that legal professionals are in a unique position to offer. It should not, however, be carried out lightly or without merit.

Firms, and those who work for them, are under a duty to the court as well as to the client. The 2012 guidance note states that firms and individuals must treat clients fairly and protect their interests in a matter. Clients must also be in a position to make informed decisions about the services they need, how their matter will be handled and the options available.

Litigation, therefore, should only be undertaken when:

- a valid claim exists

- it is in the client's best interest

- the claim has already been rejected by the lender's own processes, or their time limit to reply has expired 18

- the client is fully aware of the potential risks of litigation.

Stages of litigation

The overwhelming majority of PPI cases are settled before trial. We asked firms about the percentage of their PPI claims that reached different stages of the litigation process:

- 16 firms stated that they did not issue proceedings in any of their cases.

- 18 firms had no cases that had reached a court hearing.

- 18 firms had not taken any cases to full trial.

Two firms were litigation specialists, but, even then, only 17 cases had reached a hearing of any kind.

Volume of successful litigation

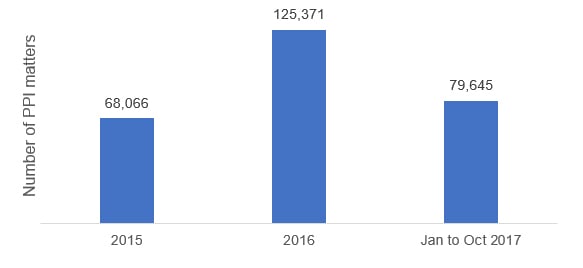

We looked at the volume of PPI litigation cases handled by firms over the last three years. The majority of firms did not engage in this activity, although as the table below shows (using figures supplied by firms) there has been an increase over time.

| Year | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 (Q1 to Q3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of firms | 3 | 5 | 5 |

| Number of litigated cases | 147 | 395 | 405 |

| Successful cases | 123 | 344 | 163 |

Significantly, 349 of the 395 cases issued in 2016 were carried out by one firm. It is important to highlight that the lower number of successful cases in 2017 may be because it is not a complete year and they have yet to conclude.

Firms have, therefore, had high success rates when litigating PPI claims. The success rate is a factor in helping to demonstrate that the decision to litigate a PPI matter is in the best interests of their client. The key issue is, however, whether clients are in a better position going through the FOS's process or litigating a PPI matter. Success rates, the amount of redress awarded, time taken and costs must all be taken into account.

Litigation factors

Before deciding whether it is in the best interest of the client to litigate a PPI claim, firms took a number of factors into account. These included:

- the type of claim

- the strength of the evidence

- the amount of the claim. At one firm, if the value of claim was less than £10,000 it would not litigate the matter and advised the client to go to another firm.

Client explanations and authority

Firms that litigated PPI claims explained the risks of litigation to clients by having a detailed discussion by phone and discussing issues such as after the event insurance (ATE) 19 and costs. Firms would then follow up the conversation in writing by sending out their terms of business/client engagement letters or a letter of advice explaining the litigation process and the costs involved. One firm sent clients a detailed letter of all the information about the hearing and the associated risks and costs.

Firms sought client authority before commencing litigation by making sure that:

- the client signed the statement of truth on the claim form or the particulars of claim

- litigation was covered by the express authority received from the client at the start of every case

- the client signs a second letter of authority, which specifically covered litigating the PPI claim.

Given the availability of FOS to resolve PPI matters, we expect firms that issue proceedings in PPI matters to act in the best interest of each client when they do so. We also expect that they have clearly explained the basis of that decision and the risks and costs involved to the client in a clear way and receive authority to do so.

Effect of Plevin on volume of litigation

The decision in Plevin has raised the possibility of future PPI claims being resolved through litigation, given the levels of commissions taken into account when considering fairness and redress. Under FCA guidance, 50 percent is deemed to be the ‘tipping point' at which the level of commission becomes unfair, and anything above this must be repaid. For example, for a single PPI premium costing £1,000 any commission over £500 would need to be repaid. In relation to litigated claims, however, there is no such threshold, so clients could potentially claim the whole amount back.

Firms were asked about the impact of the decision in Plevin on PPI cases and provided a variety of responses:

- No impact at the time of interview, as cases had been on hold until further FCA guidance was received.

- Previous clients whose PPI claims have been refused have not come back for a Plevin claim.

- A firm claimed that lenders have become harsher since the ruling and are making lower offers in the hope that clients will accept something. Some firms, however, said that lenders will pay more if litigation is commenced and this is the advice that they are providing to clients.

- Firms are still considering their options and taking advice from counsel. They do not believe that the matter has been satisfactorily concluded yet and will continue to monitor their position. One of the issues firms historically faced was the unwillingness of lenders to disclose the level of commission received. One firm said it was currently working with counsel on the position it takes with cases where the commission is less than 50 percent. The firm believes it can potentially litigate these cases and try to claim the full amount of PPI paid and seek full redress.

- Very little impact as the firm had not received many Plevin cases, and those that the firm had were of poor quality which were rejected after the vetting process.

Another advantage of litigation, from the client's point of view, was that at the time of our review the amount of recoverable commission in Plevin cases was not capped. This meant that clients could potentially receive larger sums of redress.

The responses from firms suggest that there is the possibility of further litigation around Plevin PPl claims in future months.

Good Practices

- Considering whether litigation is in the client's best interest.

- Giving the client a clear explanation about the risk involved, the possible cost consequences and why the firm considers litigation to be in their best interests.

Poor practices

- Not giving consideration as to whether litigation is in the best interest of the client.

- Issuing proceedings without properly informing the client and gaining their authority.

- Failing to provide the client with enough information to make an informed choice.

Alternative business structures

Key findings of the thematic review

- Concerns about CMCs converting into ABSs to avoid FCA regulation seem to be unfounded. We found that only a very small number of firms have taken this step and only two such firms were in our sample.

- Only one ABS shared information with a related company, and did so after gaining client consent. They had numerous safeguards to prevent unauthorised access to client data.

Lenders have expressed concern to us that the government's proposals might lead to CMCs forming ABSs to avoid FCA regulation and, in particular, the fee cap. We wanted to test this view and check that appropriate practices were in place and conduct standards were being met. We also reviewed information about confidentiality and informed consent and if and when ABSs used clients' information.

Profile of ABSs we visited

We visited eight ABSs and, despite lenders' concerns, only two firms in our sample had previously operated as a CMC. Outside the sample, we examined data we held about the legal businesses we regulate and found that there had been very few CMCs converting to ABSs in the past year. The remaining ABSs in the sample had been set up to allow non-lawyer management or were subsidiaries of other professional entities.

The ex-CMCs told us that they had become ABSs to bring PPI work in-house. Both entities believed that they had a unique commercial offering. Their ABS status allowed them to enhance the customer experience and set end-to-end service levels. It also enabled the entities to retain more of the profit from the work.

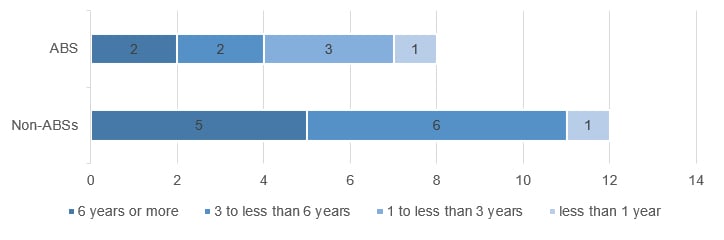

We also found that most ABSs had been trading for more than one year, and had therefore come into existence before the fee cap consultation.

How long have you been in the PPI market?

Operational differences

Like traditional firms, ABSs relied on online advertising and referrals/introducers.

ABSs allow firms to offer legal and other professional services. However, firms are still under a duty to maintain client confidentiality, even within group structures. In particular, all client information is confidential unless disclosure is required or permitted by law or the client consents 20. In addition, firms should also make sure that they have systems and controls in place for identifying and responding to risks to client confidentiality 21.

We found only one ABS that shared client information with a related company or business. Significantly, the firm sought consent from clients to share their information and also had numerous systems and safeguards to prevent access to client data.

Some ABSs we encountered relied almost exclusively on parent or group companies for their incoming work. Firms that take this approach should be mindful of their obligations regarding independence under Principle 3 and Outcomes 9.1 and 9.2.

Good practices

- Storing and managing confidential information in a compliant way.

Poor practices

- Firms being solely dependent on a linked entity to provide work. This creates a risk of the firm's independence being compromised.

Insolvency cases

Key findings of the thematic review

- In most insolvency cases, the client was not the PPI policy holder but an insolvency practitioner seeking to maximise returns on their assets for the benefit of all creditors. This fundamentally changed the nature of the case.

- Firms that specialised in insolvency often made speculative claims. This was because they acted for insolvency practitioners rather than PPI policy holders, and may have had difficulty in getting information.

- Firms specialising in insolvency work kept the policy holder informed of what was happening. Making contact in this way helped them if the lender needed any further information or evidence.

- Offset of redress is more common in insolvency cases, but firms were more experienced in challenging it.

Solicitors must act in the best interests of each client and provide them with a proper standard of service. This is particularly important when solicitors are acting for vulnerable clients, such as those in IVAs or who were bankrupt.

We met with eight firms who had acted for individuals in an IVA or bankruptcy. Four of these firms receive work directly from insolvency practitioners and two of these firms carry out this work exclusively.

In general, IVA and bankruptcy work was not deemed to be a profitable exercise unless firms specialised in this area. Numerous firms told us that they would prefer to avoid acting on behalf of individuals in an IVA or bankruptcy because lenders would inevitably seek to apply offset to any compensation.

Interestingly, the firms that specialised in IVA/bankruptcy work told us that they had developed expertise in challenging attempts by lenders to apply the offset. One firm showed us data which suggested they were 33 percent more likely to be able to successfully challenge offset than their insolvency practitioner counterpart due to specific insolvency legislation.

Lenders' concerns

We have received concerns from lenders that:

- work was carried out without their customers' knowledge

- some firms were sending large numbers of speculative claims.

Having reviewed these areas, our research suggests that the concerns may be due to a misunderstanding about the identity of the firm's client and the nature of the work.

The relationships between the parties involved in a PPI case are different where the policy holder is insolvent:

- During an IVA or bankruptcy, insolvency practitioners and trustees in bankruptcy have an obligation to realise the assets of an individual in bankruptcy or a company in liquidation for the best possible price 22. This includes investigating whether the insolvent person was mis-sold PPI.

- If a PPI policy was mis-sold prior to a bankruptcy, the claim vests in the trustee in bankruptcy. This is because the law states that the contract is an asset in the bankruptcy, as is the right to complain if it was mis-sold 23. If successful, the PPI refund cannot be returned to the consumer under any circumstances but vests in the trustee in bankruptcy or Official Receiver.

- If a PPI policy was mis-sold prior to an IVA, the claim may be investigated by the consumer, but the benefit from the claim usually goes to an individual's creditors.

In light of these circumstances, the client in an IVA/bankruptcy is usually the insolvency practitioner, notwithstanding that the financial product and PPI was initially bought by someone else.

Why might firms make speculative claims?

The two firms that carried out work exclusively for insolvency practitioners told us that the relationship between each insolvency practitioner and PPI policy holder affected how the PPI work was carried out.

As the policy holder was the insolvency practitioner's client, they had no direct agreement with the firm. This, together with the emotional strain that often occurred during a bankruptcy/IVA, meant that the insolvency practitioner's client may be unwilling or unable to provide specific details about their historic banking arrangements. This often led to the firms being instructed to act on very little information.

The two firms who specialised in this area told us that they wrote to the policy holder at the outset of the claim to tell them what was happening. This is good practice and helped the firms if they needed to ask the policy holder for more information as the claim progressed.

Having reviewed this area, we accept that, occasionally, claims may need to be made where little information is held. In particular, we recognise that insolvency practitioners and trustees in bankruptcy are under a statutory duty to maximise the assets of the debtor and therefore speculative claims by firms are inevitable. Firms should, however, make every effort to get as much information as possible before submitting a claim.

Value added?

We were particularly interested to understand why firms carried out this work. Firms told us that the DBA arrangement has made the process desirable for insolvency practitioners and trustees in bankruptcy. In particular, it allows insolvency practitioners to meet their statutory duties but also minimise and reduce their own costs. This helps to reduce the costs of an IVA or bankruptcy and maximises the assets for the creditors. Provided that the firm's costs are reasonable, the insolvency practitioner, PPI policy holder and creditors can all benefit from this arrangement.

Good practices

- Making every effort taken to gather all relevant information from insolvency practitioners and their clients.

- Having the appropriate knowledge and expertise to advise insolvency practitioners about discrete areas of PPI/insolvency work, including knowledge about offset and how it applies to individual in IVAs and bankruptcies.

Poor practices

- Failing to keep the bank's customer informed about ongoing PPI work. Although the insolvency practitioner/trustee in bankruptcy is aware of the work, the bank's customer is left in an uncertain and often anxious state if the bank contacts them.

Training and supervision

Key findings of the thematic review

- Most fee earners had received training on PPI matters within the last six months.

- Four fee earners, for various reasons, had never received any PPI training.

- All fee earners had clear lines of supervision.

- Most firms supervised through file reviews, though these varied in regularity. An equal number of firms used direct supervision.

Principle 5 states that firms must provide a proper standard of service. The following outcomes are also relevant here:

- Outcome 7.1: having a clear and effective governance structure and reporting lines

- Outcome 7.6: training individuals working in the firm to maintain a level of competence appropriate to their work and level of responsibility

- Outcome 7.8: having a system for supervising clients' matters, to include the regular checking of the quality of work by suitably competent and experienced people.

These applies equally to all work, including PPI.

The 2012 guidance note states that firms must make sure that their service is of a proper standard. This involves making sure that staff dealing with claims receive proper training and supervision.

Staff qualifications

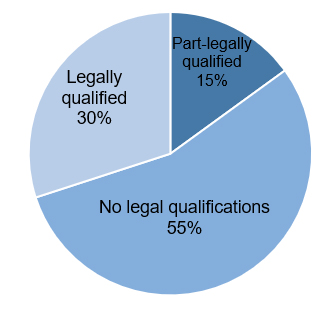

The fee earners we met were a mix of legally and non-legally qualified staff. As the chart below shows, more than half were non-legally qualified. Two fee earners had relevant financial qualifications. Some were part-legally qualified, for example they were Legal Practice Course or Bar Professional Training Course graduates. The post-qualification experience (PQE) of legally qualified fee earners ranged from three to 12 years.

Training

Training took a variety of forms. These included:

- on the job training, including shadowing more experienced colleagues

- an induction or initial training period with an increasing responsibility for work

- written resources and training guides

- ongoing refresher training.

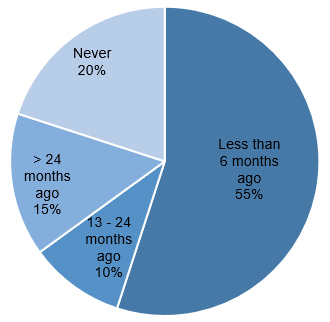

We asked fee earners when they had last received training in PPI work.

As the chart shows, most of the fee earners had received training within the last six months. This could be for a variety of reasons including:

- new starters

- refresher/update training

- the introduction of the FCA's guidelines on Plevin claims in recent months

- providing training in preparation for our visits.

However, some had not received training for almost two years. Four of the fee earners we met said that they had never received specific training. The reasons for this were:

- they are winding up their PPI business, but staff involved in the work remain heavily supervised

- the firm comprised two fee earners who had been working in the area exclusively for several years and were active in litigation, which kept their knowledge up to date

- the solicitor, a sole practitioner, had been trained in other areas such as personal injury and kept their knowledge up to date via relevant articles and decisions

- the fee earner had a strong background in insurance and had worked at a CMC. They also had experience of other types of financial mis-selling work.

All firms, whatever their size, need to make sure their fee earners are properly trained.

Supervision

Among the firms we visited, fee earners working on PPI claims generally had clear lines of supervision. The person with responsibility for supervising this work varied depending on the size and type of the firm. Supervisors included:

- managing directors or partners

- compliance officer for legal practice (COLP)

- solicitors

- team leader or team manager

- peer supervision, either because of the size of the firm, or because of the way the teams are structured.

The firms we visited used a variety of methods for supervising the work of their fee earners, and generally used more than one. These were:

Frequency and basis of file review

There was a relatively wide variety in the frequency and volume of files being reviewed, with some firms reporting that files were reviewed daily, while others said a review took place only once a month or less.

Some firms had a senior person reviewing all files, while others only sampled a small number. The regularity and method of review depended on the size of the firm and its case load, knowledge and experience of the fee earner and the complexity of the cases. However, firms should make sure, particularly where file reviews are the sole means of supervision, that they are satisfied they are supervising cases appropriately.

Some firms reported that, as they were so small, supervision happens organically as the whole team were sat together with ongoing discussion about cases. One potential disadvantage of this approach is that staff may not feel comfortable raising issues in front of others, so it should not be relied on alone. Other firms had more formal, individual meetings on a regular basis. Several firms reported that they use the reporting function of their case management system as a form of supervision. This will be helpful in identifying exceptions in terms of following correct process and adhering to timescales. However, it is not clear that this form of supervision will be able to assess the content and quality of correspondence with clients and lenders, and this should not be overlooked.